Developing the Right Test Documentation

Back in 2018, I wrote about the importance of appropriate test documentation and emphasized the need for a lean approach:

Focus on the smallest amount of documentation you need to do your job well. You have a finite amount of time and if you spend too much of it creating documentation you will have less time to do the work.

Working in startups, you place a big focus on impact and effectiveness. Depending on where you work and the answers to the below questions, you might focus on other areas and end up with different policies about the right test documentation.

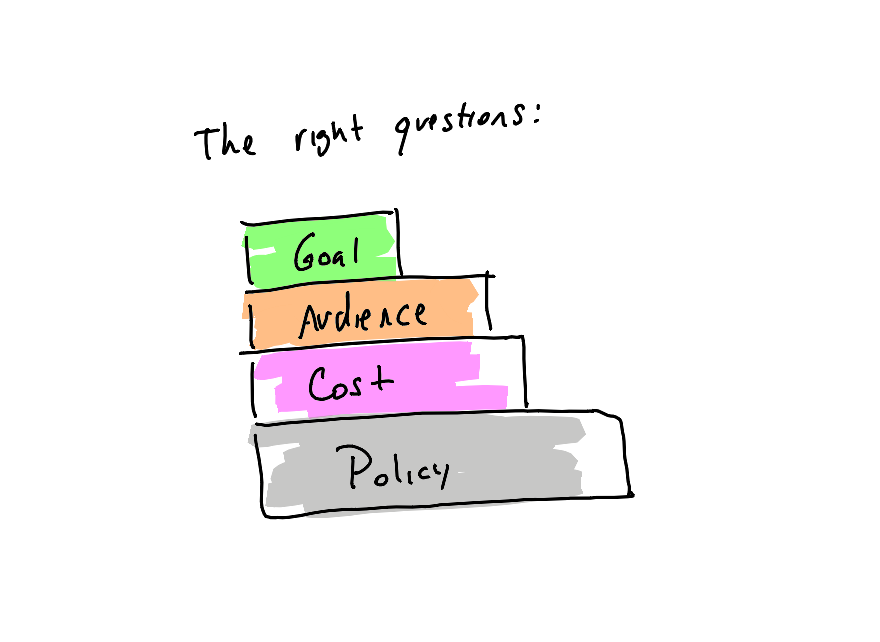

Having said this, the right test documentation is the one that satisfies the goal for the right audience and at the right cost. More often that not it means focusing on the smallest amount of documentation you need to do your job well.

The Goal

Anytime we write (test) documentation we need to understand what we are trying to achieve with it. Are we trying to solve a problem? Convey something? Ask a question? Process our thoughts?

Given a clear enough goal (even if that goal is just to write for self-reflection), we should be able to understand our audience.

The Audience

Take for example the goal of “document how the feature works”. We can assume the inherent audience is ourselves (or our team). To accomplish this goal we might describe how to configure the feature and list a few values it takes. Then, provide minimal context about its purpose and link to the originating documentation.

If the goal slightly changes to “document how the feature works, for our customers”, we’d go to greater lengths given the different audience. We might hire a professional writer (technical writer), provide the appropriate context to help the customer understand what they are reading and use a tone that’s consistent with our other customer docs.

The same goes for test documentation, who are the primary readers? Us? A customer (who might get a test report)? Are we helping the team dogfood our application? Or are we delivering feedback to internal stakeholders? It might be one or more, but it’s important to remember the audiences will be different.

The Cost

Documentation takes time and effort and therefore has some kind of cost. Both the cost to create it and to maintain it. How do we make sure our money is well spent?

We should focus on making sure that documentation is effective. We can do that by asking ourselves some follow up questions:

- Are we using the right test documentation in the right places? (Rather than some standard form or template all the time)?

- How much traceability do we need? If we are tracing to something, who controls it? (You need to be able point to specific stakeholders to justify the cost).

- How maintainable do your testing docs need to be? How long do we need them for? This will determine if the documentation cost is finite or ongoing. (Make sure you understand the tradeoffs: pesticide paradox, learning rate, etc).

Putting it All Together

Software applications are typically collections of individual systems that are mostly built by different people and organizations.

Software testing is a search for information. In order to gather information about a software application, we need a way to create a small selection of tests (or experiments) that can help us learn about the application and its systems. That test selection needs to be small enough for us to learn about the application. From there, we determine if we are getting close to our testing goal and adjust our approach if we are not.

With these principles in mind, how do we take a complex and intricate set of systems and build a sampling strategy that realizes our testing mission?

We need to create models, document product systems, identify potential risks and generally use tools to help us manage the complexity of the system and distill that complexity down into something we can think through. Lots of this involves creating some kind of test documentation:

- Charters

- Decision Tables

- Data Flow Diagrams

- Risk Lists

- Mindmaps

Once we think we understand the problem space enough, we need to figure out which tests should be applied and how. This might end up as:

- Code

- Procedures

- Tables

- Lists of Test Ideas

- Coverage Maps

There are so many more ways documentation can be used as tools to help us test. The challenge is finding the right way to use documentation as a tool to help us achieve our goals ( documentation goal and testing mission)

The Right Policy

As a manager of testing teams, I have long argued that in most cases, writing all or most test documentation as procedures is an unnecessary cost. The individual tasked with testing the application needs to identify what they should do and find the most effective way to do it. That involves building the right testing documentation for that particular need.

This brings us back to the core principal quote above:

Focus on the smallest amount of documentation you need to do your job well. You have a finite amount of time and if you spend too much of it creating documentation you will have less time to do the work.

Ultimately, by applying this policy—focusing on the right documentation for the right goal, audience, and cost—we don't just write better docs. We build better software by spending our time on what truly matters: effective testing.

Member discussion